Lately, I’ve been watching the same episode of It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia over and over simply because it brings me joy. Although I have viewed it over ten times since the semester began, rewatching the episode does not get old. This is a phenomenon that I do not understand; never before have I watched a single episode that many times. Therefore, I am embarking on a quest to analyze this episode in-depth by utilizing my MCM brain. Prior knowledge of It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia is highly recommended before reading this fine literature. If you don’t have prior knowledge of the show or the episode, scroll all the way to the bottom of the article so I get a lot of views. Thank you.

The episode begins at 7:15PM on a Friday, suggesting that one Charlie Kelly has nothing better to be doing on a Friday night. No rats to be bashing? No trash to be burning? Nay. Rather, Charlie has been working on a musical, stating that he has no ulterior motive. We will later find out that this is not the case.

It is important to note that the bar is completely empty at 7:15PM on a Friday. Perhaps this is due to the condition of the bar and the narcissistic bar owners who are completely lacking in customer service skills. More likely, the bar is empty because the construction of Philadelphia as exemplified in this show is fake. Life, like time, is an illusion.

We move to the opening credits, which contain a curious distinction. The show is said to be “starring” Charlie Day, Glenn Howerton, Rob McElhenney, and Kaitlin Olson. Next, “And Danny Devito as “Frank Reynolds.”” What? Why is his name in quotations? Is Frank real? Perhaps, Frank, like life, and also time, is an illusion.

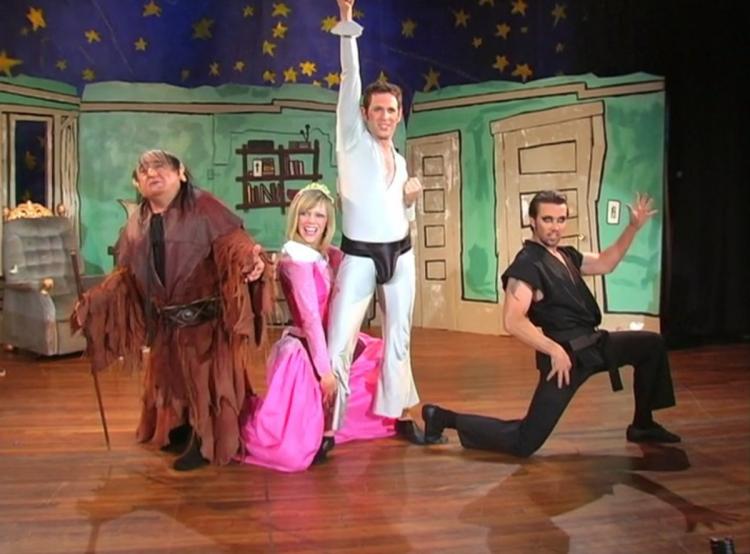

Action begins inside the local theater, pronounced ‘thee-ay-ter’ by Director Charlie. He distributes scripts to the cast members. The script’s cover illustration is clearly evocative of Van Gogh’s Starry Night, due to the similar color pattern and somewhat disjointed lettering like the swirling sky. As the viewer will come to understand, the musical deals intensely with themes of belonging, identity confusion, and personal growth, like Starry Night represents Van Gogh’s quest to overcome illness.

Next, Sweet Dee and Dennis rehearse the first song of the musical, which Dee views as inappropriate. She states, “he wants me to bang this baby and I don’t feel comfortable.” The confidence reflected in her tone disrupts the male spectator’s voyeuristic experience of the episode, as he identifies with the strong male figure of the baby boy played by Dennis. Sweet Dee is a strong female character, a threat to the male ego. Charlie argues that the baby referenced in the song is a metaphor for the spirit of the boy, that he is in fact a man, thus building up the male ego again. Dee states that she isn’t convinced Charlie knows what metaphor means. Language? Yeah, you guessed it. Also an illusion.

A shot to analyze:

Note the presence of the ladder, suggesting immediate danger. The mirror behind Charlie functions to include something we otherwise would not be able to see: the back of Charlie’s head, and therefore, the rest of that amazing director’s hat. I was definitely curious about what it looked like. Thanks, mirrors. Oh, yeah. Mirrors? Reflective surface. Also an illusion.

Finally, Charlie descends from the ceiling in a yellow suit, as the Dayman. He has aged and lived as Dayman, and is now ready to marry Charlie’s real life love, the Waitress. This possibility of true love and happiness emanates from the Dayman’s strength and power, which the male spectator experiences as his own. Furthermore, distinction between real life (illusion) and the musical (illusion within an illusion) has completely disappeared. Waitress says no, Charlie is heartbroken, elderly audience goes home. The end.

In conclusion, life, time, Philadelphia, “Frank,” language, and mirrors are all illusions. Nothing is real. Freud’s theories are valid, as the male spectator identifies with the baby boy who achieves success as the Dayman, but is ultimately 1) confused due to rapid aging and 2) disappointed by the Waitress in a showing of female strength. This, along with Sweet Dee’s strength, addresses something left out of psychoanalysis: the experience of the female-identifying spectator. Therefore, this episode does not get old due to my own identification with the female figures. Case closed.