Warning: minor spoilers for crappy rom-com books and movies.

I’d like to start off by defining the term Manic Pixie Dream Girl (MPDG). MPDGs, as defined by TvTropes.com, are female characters that exist simply to help the protagonist (note: male) achieve his own goals. She does not pursue any goals of her own. She must be extremely attractive (although extra points are awarded if she’s ‘unconventionally attractive,’ a.k.a .extra doe-eyed, has purple hair) and posses plenty of wacky quirks like having a mason jar collection or the ability to recite Walt Whitman’s poetry while eating cold pizza and dancing barefoot in her vintage apartment.

Basically, MPDG’s are every straight guy’s wet dream: the cool girl that likes video games and burping and is sooooo understanding.

Sounds super great, right? Everyone totally wants to date or be this girl, yeah? How absolutely tragic that most girls are basic, and only one girl in a million is beautiful AND smart AND likes pizza! Not.

So, I bet you’re thinking: Nicole, why does this matter? Aren’t there more important issues than sloppy writing? Well, friend, you’re not entirely wrong! But fiction is consumed on a widespread and daily basis by society. Books and movies impact us in subtle and in astronomical ways. MPDGs in popular, mainstream works serve to perpetuate idealistic, static presentations of women. And we really don’t want that.

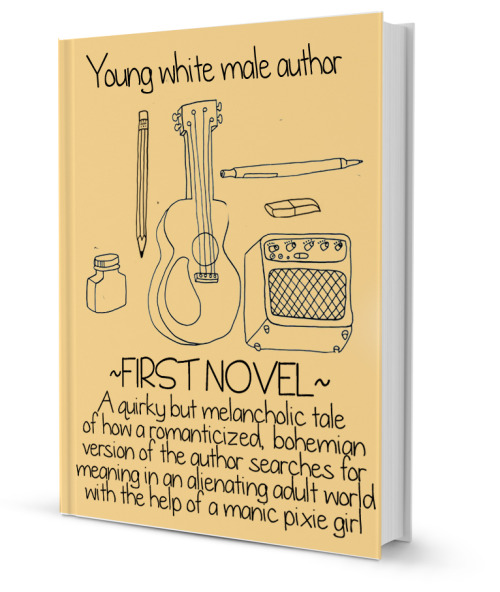

I’d like to focus on one author in particular because I’m sure we’ve all cried ourselves dry over the film adaptation of The Fault in Our Stars. John Green has bestowed upon us one of the most manic of the pixie dream girls: Alaska Young, from Looking for Alaska. Johnny Boy swears that this book and Paper Towns are meant to “deconstruct the idea of the MPDG” and all that garbage, but even if that as his intention, it doesn’t come across strongly in the books. His two male protagonists spend each book fantasizing about and idolizing these girls. In the end, they’re all “this girl changed my life but she’ll never be able to escape the great labyrinth of personal suffering” or something equally pretentious.

Alaska, the titular character in John Green’s Looking for Alaska, is self-destructive, slightly enigmatic, moody, and constantly crushed beneath her own self-misery…Now, wouldn’t it seem better to “deconstruct” the idea of the MPDG by following Alaska’s journey as she attempts to grow as a person?

Nope. We get about 200 pages of your standard, broody male character being pretentious about his infatuation with this girl, completely idolizing her because she gives him the courage to be more assertive and because they have an intimate connection, blah blah blah. She’s reduced to your basic “MPDG used as a quirky plot point for the male protagonist to become a stronger person.”

One could argue that Margo Roth Spiegelman, the token MPDG in Green’s Paper Towns, confronts the male protagonist in the novel by telling him she is a real, imperfect person that shouldn’t be glorified. It’s a small victory. Yet, my friends and I didn’t get that when we first read the book. Or, rather, I feel the main character, Quentin, didn’t really take any of Margo’s statement to heart and was just like “yeah, uh-huh that’s great, can we make out now?” Blah.

If you want to look into a book or movie that really deconstructs the idea of the cool girl or the MPDG, read Gone Girl. Or watch (500) Days of Summer, which does an okay job (but even STILL some people claim he should’ve gotten the girl and I just:)

John Green is not the only fiction writer to be guilty of idolizing the Manic Pixie Dream Girl. However, his books are popular enough to serve as an example for this widespread trope. The trope is problematic because of the way it portrays girls as static, cookie-cutter people that lack emotional depth and serve only as plot points for men. It’s sloppy writing and portrays an unrealistic representation of girls. No wonder so many guys nowadays complain that girls are so “confusingly hard to understand”; they’re used to the media portraying them as two-dimensional and perfectly imperfect.

This trope, along with bad rain metaphors, ought to be demolished once and for all.